- What Is Slippage in Trading?

- Why Does Slippage Happen?

- How I Manage Slippage in My Trading

- Real Example of Slippage in Action

- Tips for Reducing Slippage

- Trade During High-Volume Times

- Use Smaller Share Size on Thin Stocks

- Always Check the Spread

- Anticipate Apex Points

- Avoid Penny Stocks With Wide Spreads

- Conclusion

One of the first trading terms I stumbled across was slippage. At the time, I didn’t think much of it until it hit me where it hurts: my P&L. Every trader runs into slippage sooner or later, and if you’re not prepared, it can make the difference between a green trade and a red one.

So, what is slippage in trading? It’s the difference between the price you expect to get and the price you actually get. That little gap can cost you pennies, dimes, or even dollars per share, and when you’re trading size, those pennies add up fast.

Slippage is the gap between expected and actual fill price. Trading is risky. Most beginners lose money, and my results aren’t typical. Always start in a simulator before risking real cash.

What Is Slippage in Trading?

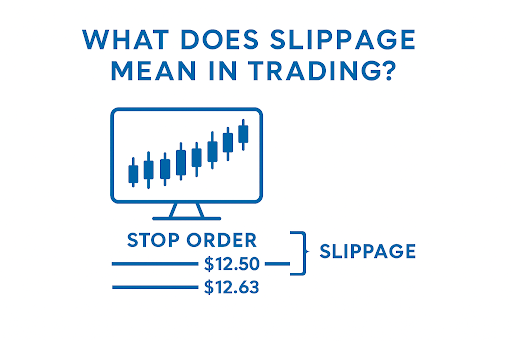

Slippage happens when you send an order, and it fills at a price different from what you planned. If I set a stop at $12.50 but end up getting filled at $12.63, that 13-cent difference is slippage. It doesn’t sound like much until you multiply it by 10,000 shares — suddenly that’s $1,300.

There are two types of slippage:

- Negative slippage: The most common. You get a worse fill than expected, usually on fast moves.

- Positive slippage: Rare, but possible. Your order fills better than expected. Maybe you sold above your limit because someone stepped up with a higher bid.

The reality? Most of us deal with negative slippage, especially when trading momentum.

Why Does Slippage Happen?

Slippage doesn’t happen randomly. It has clear causes.

- Fast-moving markets: If a stock rips through resistance, orders stack and the price skips levels. By the time your order hits the market, it fills at the next available level.

- Low liquidity: Thin order books can’t absorb big orders without moving prices. Market makers will clear the book; then, the stock fills back in.

- Market orders: These guarantee execution but not price. If there’s no one sitting at your target level, you’ll get filled wherever the liquidity is.

- Stop orders: Most stop losses are designed to convert into market orders once triggered. That means you can slip badly in a fast drop.

I’ve seen it countless times:

If you hit a market order exit with a large position, it can cause momentary flash drops as the market makers clear the book, then it fills back in.

This is why trading low-float momentum stocks comes with added risk. When a stock breaks half-dollars or whole-dollars with thin liquidity, the slippage can be brutal.

How I Manage Slippage in My Trading

Over the years, I’ve learned you can’t eliminate slippage, but you can manage it.

Here’s what I do:

- Use marketable limit orders. I’ll set my limit a couple of cents above the ask when buying, or a couple of cents below the bid when selling. That way, I get filled quickly but with some control over price.

- Avoid live stop orders . I keep mental stops and use hotkeys to bail. If you leave stop orders sitting out there, they can be swept.

- Trade liquid names. Stocks with high volume and tight spreads usually have less slippage.

- Scale out into strength. Instead of dumping size on the bid, I take profit into buyers on the ask.

The best setups work right away. If it doesn’t, I bail.

These habits don’t make me immune, but they cut down the number of times I get caught with nasty fills.

Real Example of Slippage in Action

Here’s an example from a trade. I was short at $12.40, watching the stock drop to $12.00. My stop was set at $12.50. When it started curling back up, I tried to cover. But instead of getting filled at $12.50, I got $12.63. That 13-cent difference was pure slippage.

When you’re trading a couple hundred shares, it’s annoying. With 10,000 shares, it’s a problem. That one slip cost me more than a thousand dollars. Plus, in a short position, the risk can become amplified. Because of this, I rarely short stocks.

You’re going to have some short sellers who start to cover a little early, so they don’t get as much slippage on the breakout.

That’s why experienced traders often exit early or anticipate levels. It’s all about managing the risk of getting slipped when momentum kicks in.

Tips for Reducing Slippage

Slippage is part of trading, but you can cut it down by being smart about when and how you trade.

Here are some of the ways I manage it:

Trade During High-Volume Times

The first 30 to 60 minutes after the open usually have the most liquidity. That’s when slippage tends to be smaller because there are more buyers and sellers stacked in the book.

Use Smaller Share Size on Thin Stocks

When liquidity is limited, hitting 10,000 shares can push the price against you. Reducing size helps minimize the impact of your own orders.

Always Check the Spread

A five-cent spread may not sound like much, but when you scale in and out, it adds up. If the spread is too wide, I’ll often skip the trade entirely.

Anticipate Apex Points

Instead of chasing a breakout late, I try to anticipate the spot where buyers will pile in, usually at half-dollar or whole-dollar levels. Entering a few cents early reduces the risk of slippage.

Avoid Penny Stocks With Wide Spreads

Low-priced stocks can have deceptive liquidity. Even if volume looks high, the spread can be so wide that slippage wipes out the trade.

Conclusion

Slippage is one of those things that every trader has to deal with. It’s part of the game. The key is to understand why it happens, expect it, and learn how to manage it.

Even after thousands of trades, I still get slipped, but it’s rarely a surprise anymore. I know the conditions that cause it, and I plan around them.

If you want to see me handle this live, grab my free day trading strategy guide. And remember: trading is risky. Most beginners lose money. Always start in a trading simulator until you’re confident.