Whether it’s an orchestrated short squeeze, an outright fraud, or insider trading, the stock market is wrought with scandal and controversy. And the kicker is that the public only hears about a tiny fraction of them.

Consider how many OTC pump and dump or insider trading schemes occur every week without anyone, but the parties involved hearing about it.

Today, we’re going to review some of the more interesting narratives and stories in the stock market in recent memory.

Porsche Attempts to Takeover Volkswagen: The Biggest Short Squeeze of All Time

Back in 2005, German sports car manufacturer Porsche announced that they were attempting to acquire competitor Volkswagen. Over the following few years, Porsche acquired a large portion of Volkswagen’s public float, pushing the price up dramatically.

The vicious repricing of VW’s stock over the following months and years struck some hedge fund managers as irrational. After all, the car business is highly cyclical, low-margin, and riddled with debt. What gives?

As a result, rockstar hedge fund managers like Steven Cohen and David Einhorn began shorting VW stock, as it had become uncoupled from the automotive market’s norms. The short interest of VW climbed as the price continued to make new highs.

Time went on, and Porsche continued publicly building their stake in VW. Things continued to get worse, and short-sellers held or added to their positions. Morgan Stanley’s Adam Jonas warned clients against playing “billionaire’s poker” by shorting VW.

Then something even stranger occurred—the global financial crisis. Stock markets across the globe were in freefall, and capital intensive automakers were in big trouble. But VW stock kept going up.

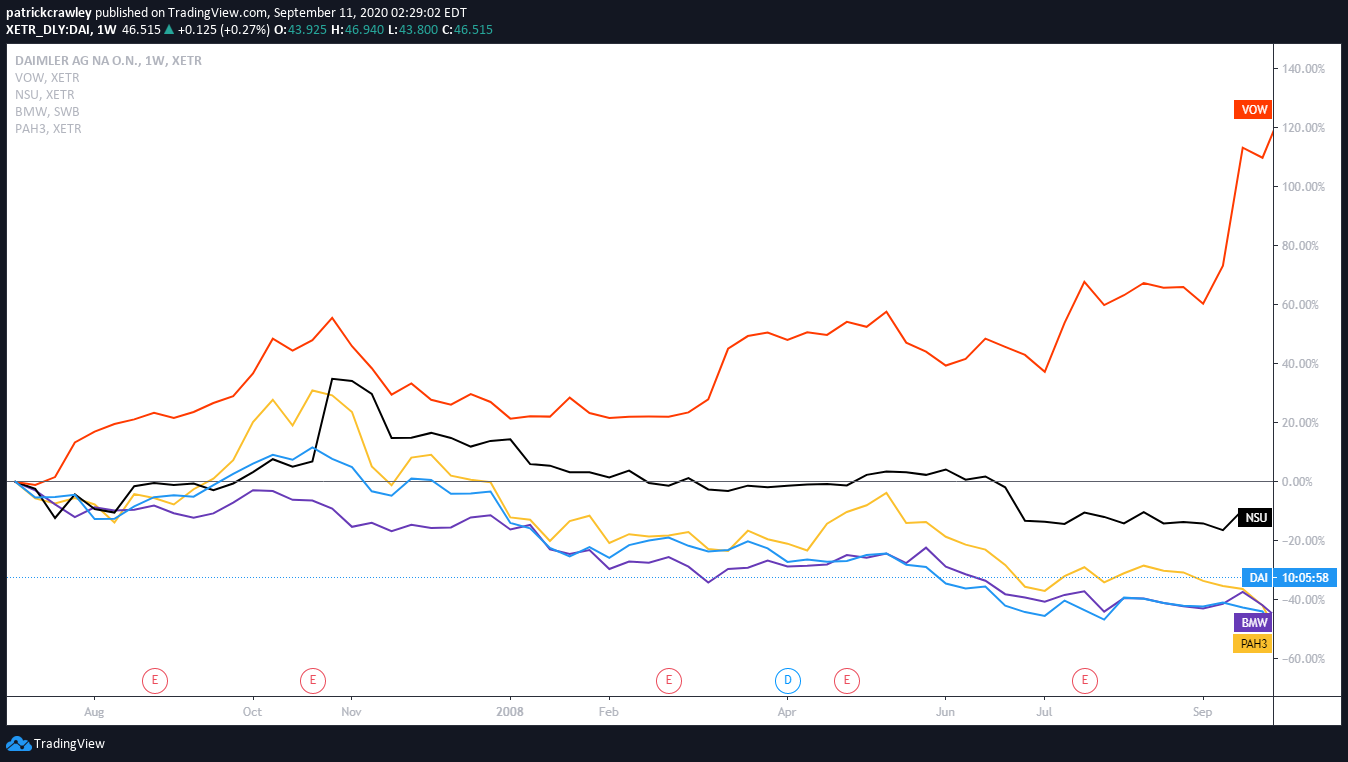

See the chart below, which compares the stocks of various German automakers throughout late-2007 to mid-2008:

Then Porsche made the announcement.

They controlled almost the entire public float of VW stock. You see, the market knew that Porsche was buying, and they thought that Porsche owned roughly 35% of VW, but then Porsche came out with a blockbuster: they controlled 74% of VW, 42.6% in stock, and another 31.5% in VW options.

On top of that, another roughly 20% of VW was owned by a German state, Lower Saxony. This left just 6% of the shares outstanding leftover.

Shorts, many of whom were receiving margin calls, were forced to be utterly price-agnostic in buying back their positions. There were almost no shares left to buy.

Here’s what happened to VW stock:

Looks more like the low-float momentum play of the week than a massive automaker, right? The stock reached a high of 1005 and briefly became the most valuable company in the world.

While this escapade is thought to have made €30-40 billion in paper gains for Porsche, reports say that their realized gain on this transaction was more in the ballpark of €6-12 billion.

However, then-Porsche CEO’s plan ended up failing. The global financial crisis worsened, and Porsche was cash-strapped. Banks weren’t lending, and they had to turn to a lender of last resort: none other than Volkswagen.

That’s right, Volkswagen ended up buying Porsche in the end.

When everything was said and done, both companies’ stocks basically went back to normal, trading in lockstep with each other.

Retail Partly Fueled the Tech Rally?

One of the prevailing narratives in financial markets over the last decade has been the death of the retail investor. The market has become so overrun by passive institutional money that everyday individual investors with $100,000 invested make a negligible difference in the stock market.

But, 2020 has seen a massive resurgence for retail’s influence on the market, but this time it’s in the options markets and tech stocks.

To start, volumes in tech stocks have exploded following the coronavirus-related market crash in February and March 2020. The narrative around these gains is that tech is still growing fast, and is relatively unaffected by lockdowns. Many of them see surging revenues due to an increasingly work-from-home population.

Below is a chart displaying the severity of tech’s dominance over the stock market:

Source: SentimenTrader.com

Now let’s look at retail option exposure:

Source: SentimenTrader.com

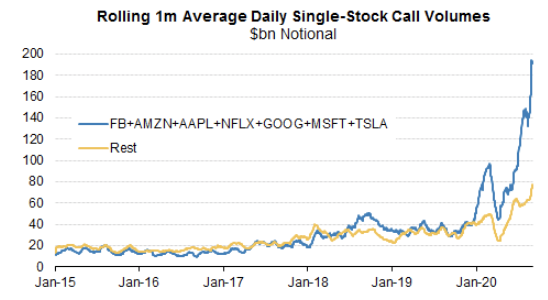

And most of that volume is in the big tech momentum names:

Source: Benn Peifert on Twitter

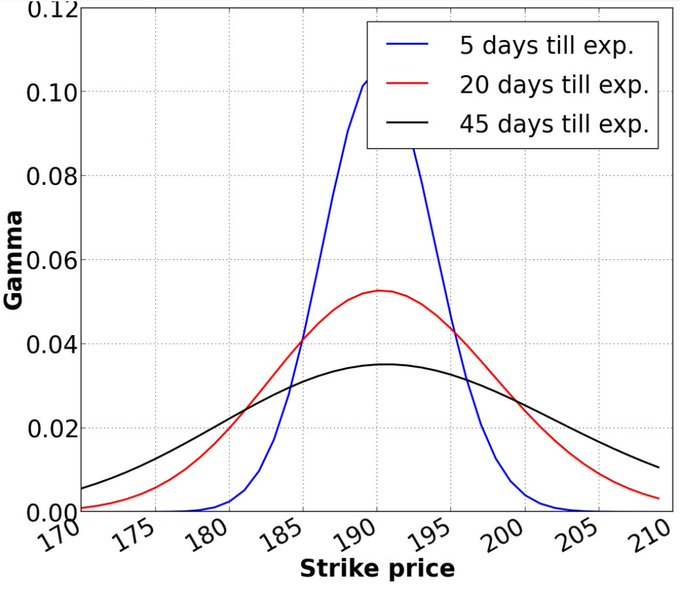

And super short expirations:

Source: Ben Peifert on Twitter

There’s a fascinating thread going around on Financial Twitter right now that tries to explain nuances of this from option trader Benn “DJ D-Vol” Eifert. Here’s the link to the thread. He describes how out-of-control the leverage on these short-dated out-of-the-money options can get.

The market makers taking the other side of these trades have to hedge their exposure through buying the underlying stock, which creates a feedback loop, pushing the stocks up and encouraging option buyers to double down.

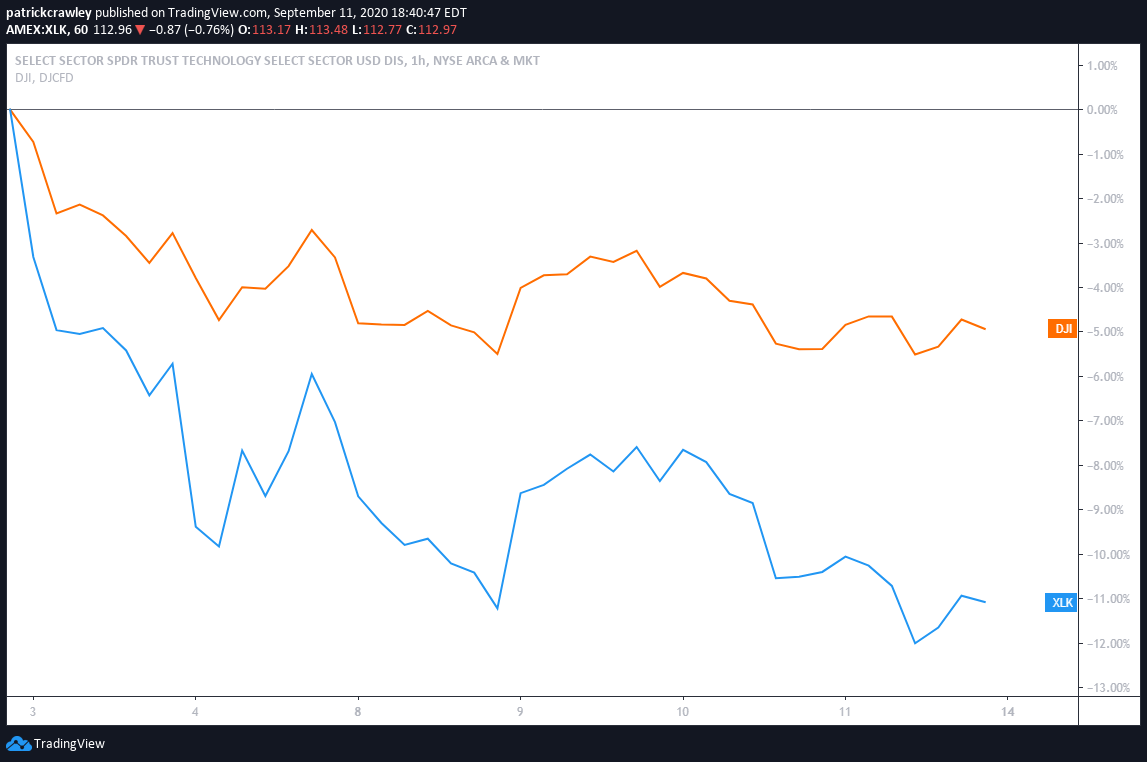

This may explain the recent sharp downside momentum in the tech sector. Here’s a chart showing the XLK technology ETF (blue) compared to the comparatively less affected Dow Jones Industrial Average (orange) since the drop began:

In another twist, many, including the Financial Times and Wall Street Journal, are opining that the Softbank Group, the parent company of Vision Fund, the world’s largest technology venture capital fund, had a hand in this too.

In the world of Financial Twitter (FinTwit), lambasting Softbank’s eccentric CEO, Masayoshi Son, is a regular pastime. As an investor in many tech unicorns with equally ridiculous CEO personalities, he’s regularly ridiculed for paying massive multiples for businesses with no path to positive cash flow.

This week, the Financial Times reported that Softbank spent $4B on tech stock options, with a notional value of $30B. Translation: this trade is/was essentially 7.5x levered.

In a nutshell, FT estimated that the rampant speculation in tech options by retail investors boosted Softbank’s massive option exposure, theoretically booking them a large paper profit before the tech correction.

However, many contradict this as a simplistic view of what’s going on.

Let me give a disclaimer that I’m no expert when it comes to the plumbing of the options markets. While there’s plenty of smart options guys who are making the case that Softbank made an immense contribution to the post-COVID momentum, there are also several intelligent people who think it’s mostly conjecture.

Crazy Eddie’s Crazy Stock Scam

“Eddie was a godlike figure to me. We all looked up to him like a leader. He worked out with weights; he carried himself like a prince or something; he was just so charismatic.” – Sam E. Antar

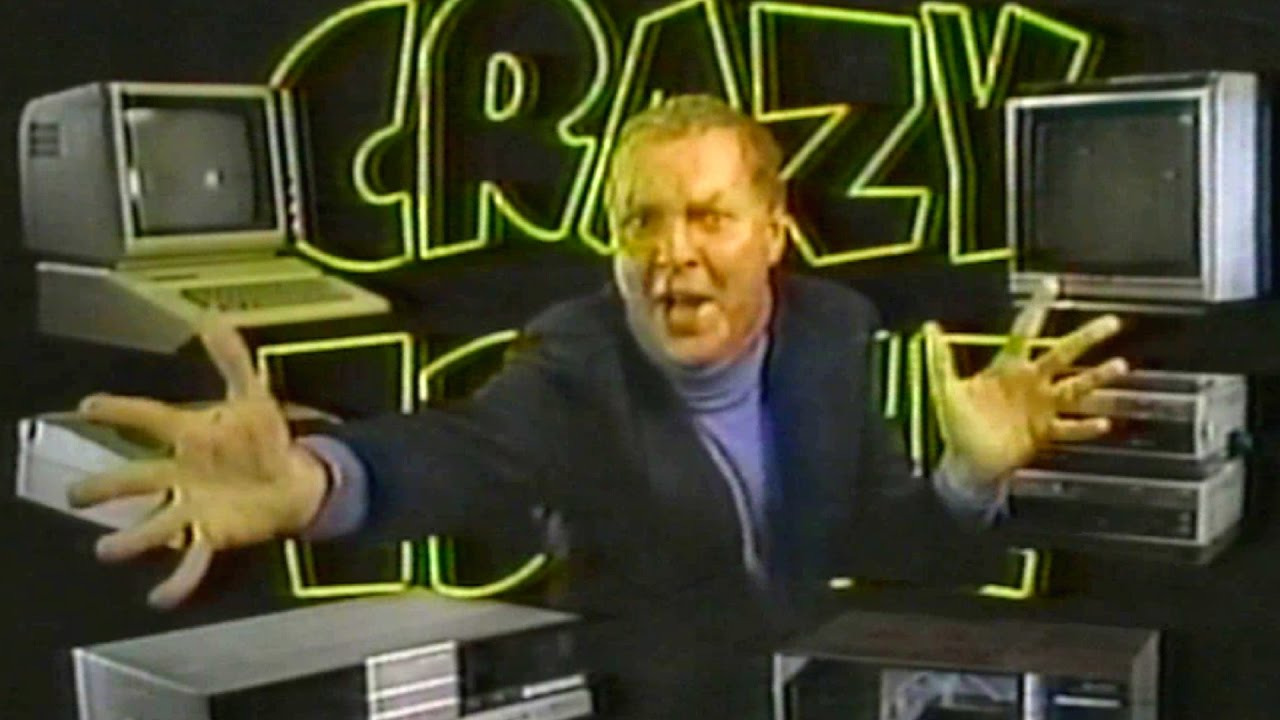

If you grew up in the New York tri-state area in the 1980s, there’s a good chance you remember Crazy Eddie. “Crazy Eddie: his prices are insane!” Crazy Eddie was a small regional electronics retailer that turned out to be a massive accounting fraud orchestrated by an uncle and nephew.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ml6S2yiuSWE

Crazy Eddie was somewhat of a fraud from the beginning. While they actually had physical stores that sold electronics, the first stage of their fraud was of the tax and insurance variety. They under-reported their income to the IRS and over-reported losses to their insurance company.

Crazy Eddie during one of his trademark commercials

Crazy Eddie’s nephew, Sam Antar, worked for Crazy Eddie’s accounting auditor, Penn & Horowitz, while secretly working off the books for Crazy Eddie to prep them for an IPO. They had to stop defrauding the IRS so they could start defrauding Wall Street.

Sam Antar later became CFO of Crazy Eddie, and they went public in September 1984.

Sam Antar cooked their books well enough to fool both their auditors and Wall Street investors. In a blog post by Antar, he displayed one massive red flag, for example. While gross profits were strongly growing, inventories were growing rapidly, and the amount of time it took to sell that inventory (days-sales-inventory, DSI) was growing at a high clip as well.

Over the three years following the Crazy Eddie IPO, the Antar family, who owned most of the company, unloaded their shares for close to $100 million in proceeds.

Their auditors actually unintentionally helped them commit fraud too. According to Sam Antar, his fraudulent accounting was so convincing that their auditors actually thought they were underreporting earnings and convinced them to be a bit more aggressive on reporting profits.

“We were so successful in overstating inventory and understating accounts payable that our auditors believed that we had substantially understated profits during the first three quarters of fiscal year 1986. Eddie and I had discussions with the auditors regarding our dilemma. The issue of accounting fraud never came up…Therefore, our auditors unwittingly helped us reduce the level of our inflated earnings by $8 million, so we inflated our 1986 income by $7 to $10 million, instead of $15 to $18 million.” – Sam Antar, former CFO of Crazy Eddie. (Crazy Eddie Fraud (whitecollarfraud.com))

The scheme finally unraveled when they received a takeover bid of $7 per share when the company was only trading at around $5 per share. Fearing that their fraud would be revealed in a hostile takeover, the family began to turn against each other.

By 1989, the chain was bankrupt and out of business. Unfortunately, I was unable to dig up a stock chart for Crazy Eddie.

Bottom Line

Of course, these stories and scandals are fun reads. However, I think they also inform us about the level of randomness in market data. If you’ve been trading for a while, you’re well aware of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), which essentially states that asset prices move in a random walk and consistent profitability over the benchmark isn’t possible over a long timeframe.

But when you read about retail traders buying so much premium that they create a positive feedback loop, or Volkswagen briefly becoming the most valuable company in the world, only to crash in the following days, it’s pretty ridiculous to buy into the theory of a perfectly efficient market.