What Are Inverse ETFs?

Inverse ETFs are a financial product that allow you to make bets against a specific asset like a sector, industry, index, commodity, etc without having to short anything.

For example, if you invested in the ProShares UltraPro Short QQQ (SQQQ) inverse ETF, you would make money when the NASDAQ 100 index (denoted by the QQQ ETF) goes down. So you can really think of it as an easy way to establish a bearish position by simply buying an ETF.

One way to view inverse ETFs is as reversed ETFs. When you buy an inverse ETF, it’s like you’re short the underlying asset, and when you short-sell an inverse ETF, it’s like you’re long the underlying asset.

How Do Inverse ETFs Work?

Before we can understand how an inverse ETF works, we have to start at how traditional ETFs operate, which is pretty simple.

So, where does your money go when you buy an ETF? If you buy shares of an S&P 500 ETF, what does that mean? How can you own 500 stocks for just a few hundred dollars?

Well, one way to think about an ETF is that it’s like a brokerage account full of shares of stock, bonds, commodities, and other assets, that you can buy a percentage stake in.

Let’s look at the popular S&P 500 ETF (SPY) as a demonstration. SPY is an ETF that replicates the S&P 500 index, which is essentially the 500 largest US stocks by market capitalization.

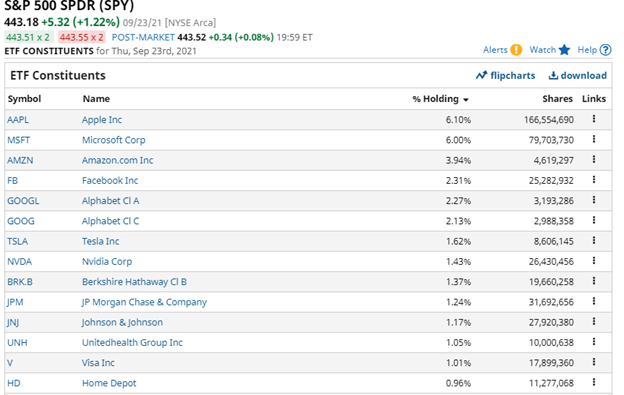

You can buy one share of SPY (at the time of writing) for $443. So what do you get for that money? As you can see in the image below, 6% of that money is in Apple stock, another 6% in Microsoft, 4% in Amazon, and so on.

It’s like there’s a massive brokerage account with all of these stocks in it and you just bought a tiny piece of it.

So moving onto inverse ETFs, they work very similarly, except the construction of the portfolio from the ETF managers is a little bit more complicated. You see, most ETFs are portfolios of long stocks, which are pretty simple to create and manage.

But inverse ETFs have to manage short positions in stocks and other assets which complicates things quickly. Firstly, most inverse ETFs suffer from significant “tracking error,” meaning that there are meaningful divergences between the returns of the inverse ETF and the portfolio it’s trying to replicate.

This occurs because inverse ETFs have to rebalance their portfolios so frequently to maintain their leverage ratio.

In other words, they have to short more stock to ensure that they’re fully invested. Oftentimes, their trading is done by mandate, not tactically, meaning that they’re forced to trade at the most inopportune times, like selling more on down days and buying more on up days.

Why Use Inverse ETFs?

Outright Short Selling is Risky

Outright short selling carries the hypothetical potential of unlimited loss and you can easily lose multiples of your initial investment. Take the famous case of the retail short seller who shorted KaloBios (KBIO) the day that Martin Shkreli gained a majority stake in the company, shooting the price up 800%.

The trader was left in significant debt to his broker.

This is where inverse ETFs carry a significant benefit, especially to risk-averse, novice investors who are afraid of short selling. Because you’re actually buying an inverse ETF, the price cannot fall below zero. The most that you can lose is your initial investment.

This might seem trivial when dealing with assets like major equity indices, but a commodity like oil can make devastating percentage moves in just a few days or weeks, increasing the allure of a built-in stop loss at the zero threshold.

You Can Use Inverse ETFs In Retirement Accounts and Cash Accounts

You can only short-sell stocks in a margin account, and because traditional retirement accounts in the United States are cash accounts, you cannot short stocks in them.

This creates headaches for investors who have been steadily adding a portion of their paycheck to the markets for years, only to see significant market turbulence around the corner, with an inability to hedge themselves against it effectively by shorting stock.

In addition to the options market, inverse ETFs provide a direct way that retirement investors can make direct bearish bets for either speculative or hedging purposes.

Additionally, inverse ETFs also come in handy for those brokerage accounts which can’t short-sell, like regular cash accounts or accounts with brokerages like Robinhood, which restrict short selling for all of their customers.

You Can’t Get a Share Locate

When you short sell a stock or ETF, you need to borrow the shares from your broker in order to sell them. That’s the process; you borrow the shares, sell them first, then you need to buy them back in the market later to repay your loan.

However, sometimes, there’s no shares for you to borrow. This could be a liquidity problem (there’s simply so few shares out there), but most often it’s a supply and demand problem, where so many short sellers have borrowed shares that your broker has no shares left to lend you. You might think this is only a problem that arises in individual stocks, but I’ve seen it happen multiple times on top indexes like the QQQ.

In these situations, you can turn to an inverse ETF, because you don’t need to do any borrowing to buy an inverse ETF.

The Drawbacks of Inverse ETFs

To the naked eye, inverse ETFs can seem like magic. They seemingly provide you with all of the benefits of short selling with none of the drawbacks (unlimited loss, locates, margin calls). However, there’s no free lunch in financial markets and inverse ETFs are no exception.

You can’t establish a short position out of thin air. If you buy an inverse ETF, there’s a lot of work on the fund manager’s side of the equation done to make that happen. And this work costs money and isn’t perfect, resulting in some shortcomings that might make you reconsider utilizing inverse ETFs next time you want to short an index or commodity.

Fees

Most standard index ETFs carry expense ratios below 0.10%, so cheap that it’s hardly worth fussing over. But that’s because those products are so comparatively easy to create and manage. They buy a bunch of highly liquid stocks and rebalance quarterly.

Inverse ETFs, on the other hand, have to hassle with illiquid and costly-to-trade derivatives, gather locates for stock, and rebalance their portfolios daily. This is all while suffering from major tracking error.

As a result, inverse ETFs require lots of legwork from the managers and hence, they carry higher fees. The typical expense ratio of an inverse ETF is around 1%, more than ten times that of SPY, which is one of the top S&P 500 index funds.

Tracking Error

Tracking error is when the performance of a replicated portfolio (in this case, the inverse ETF) diverges from the true performance of the portfolio it’s trying to replicate. For example, an inverse S&P 500 ETF is likely to perform differently than outright shorting the S&P 500 for a barrage of reasons of which we’ll get into.

Tracking error is unavoidable. You can think of it as the cost of implementation. When you compare an ETF to it’s underlying index, you have to remember that you cannot trade an index directly.

An index is simply a mathematical calculation based on the performance of the stocks in the index. An ETF actually buys and sells said stocks at arbitrary prices, which creates the tracking error.

So every ETF, even simple ones like SPY or XLF experience tracking error, but it’s much more of a factor with inverse ETFs.

While there’s a litany of factors that contribute to inverse ETF tracking error like trading costs, fees, not being fully invested, using derivatives instead of shares, etc., the overwhelming cost that creates the significant tracking error in inverse ETFs is how frequently they have to rebalance.

While traditional ETFs typically rebalance quarterly, inverse ETFs are forced to rebalanced daily to maintain their leverage ratio. This issue is compounded if you’re dealing with a leveraged inverse ETF.

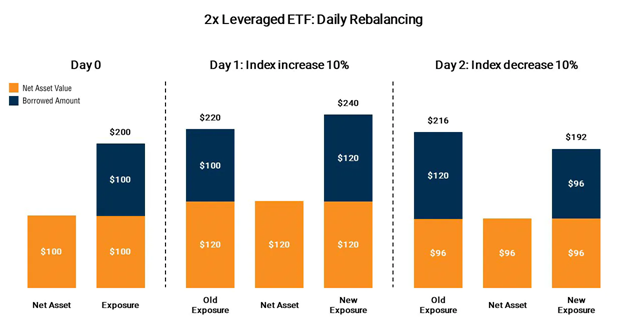

Here’s an excellent graphic from Joel Lim illustrating the handicap of inverse or leverage ETF tracking error:

The above graphic is for a 2x leveraged bull ETF, which is not an inverse ETF, but the concept works the same way for leveraged and inverse ETFs.

As you can see, the net asset value of the leveraged ETF starts at $100. On day one, the index increases 10% and the net asset value of the ETF increases to $120. Now that the NAV is higher, the fund must borrow more cash and rebalance the portfolio to hold $240 worth of stock at the end of the day. On day two, the underlying index falls the same 10%, bringing the NAV to $96.

You can already see a sizeable tracking error in just two days of trading (even though the percentage moves are magnified), so imagine how much that issue compounds over months or years.

Not For Long-Term Use

The prospectus, which is the document with all relevant disclosures about a security offering, of nearly every inverse ETF stresses that they are not to be used for long-term investing, but instead for short-term hedging and speculation. This is primarily because of the tracking error.

Here’s a short excerpt from the prospectus of rhte ProShares UltraPro Short QQQ (SQQQ) leveraged inverse ETF:

“ProShares UltraPro Short QQQ® (the “Fund”) seeks daily investment results, before fees and expenses, that correspond to three times the inverse (-3x) the return of the Nasdaq-100® Index (the “Index”) for a single day, not for any other period. A “single day” is measured from the time the Fund calculates its net asset value (“NAV”) to the time of the Fund’s next NAV calculation. The return of the Fund for periods longer than a single day will be the result of its return for each day compounded over the period. The Fund’s returns for periods longer than a single day will very likely differ in amount, and possibly even direction, from the Fund’s stated multiple (-3x) times the return of the Index for the same period. For periods longer than a single day, the Fund will lose money if the Index’s performance is flat, and it is possible that the Fund will lose money even if the level of the Index falls”

Bottom Line

As you can see, inverse ETFs are very complex securities that aren’t meant for most investors. They were created for very specific short-term trading purposes by expert traders and investors. You won’t be finding any financial advisors recommend this for your retirement account anytime soon.

However, with all of their drawbacks, it’s important to note that inverse ETFs simply provide another option for crafting a position. They’re good at achieving their limited use-case of hedging or speculating for one trading day.

To summarize, here is a brief list of pros and cons for inverse ETFs:

Pros:

- You can “short” something without unlimited risk

- They’re easy to trade and available to nearly all account types

Cons:

- They’re only meant for very short-term trading

- Very high fees

- Complex products that are difficult to understand

- Significant tracking error